Antibiotics are the foundation of modern medicine. We need to ensure it stays that way.

Across the world, drug-resistant infections are on the rise. Meanwhile, investments in the antibiotics needed to control them remain dangerously low, too low to change that.

Business as usual is not enough. In the run-up to the United Nations General Assembly High-Level Meeting on Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR), GARDP and other organizations are coming together to raise awareness on the need to invest in antibiotic research and development.

The race is on.

No one is safe

Meet the people affected by antibiotic resistance.

Melissa's story

Melissa Nelson is a disease intervention specialist with the Jefferson County Department of Health, in Birmingham, Albama, USA. When someone is diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection, it is Melissa's job to investigate from where it has come and to stop it from spreading further.

"People affectionately call us 'sex detectives'," she says.

When engaging with young people who feel invincible, Melissa asks them, "What would you do if we started to see a drug-resistant strain of gonorrhoea here in Birmingham, Alabama? Because it exists."

Ashish's story

Dr Ashish Abraham runs medical camps in villages in Madhepura, a rural district in the state of Bihar in northern India, to offer care to the Musahars, part of India's "Scheduled Castes" (i.e. the lowest caste, formerly "the untouchables").

It was during one of these health camps that Ashish found a child with Mycetoma, also known as Madura foot, caused by actinomyces bacteria. It would take several months of antibiotic treatment to fight off the infection.

"We've started building rapport and earning trust," says Dr Abraham. "That is the first step in providing the Musahars with accessible healthcare, including effective treatment of bacterial infections."

Hilary's story

As an oncologist in the UK, Hilary had treated thousands of patients for cancer over the years, but nothing prepared her for her own cancer diagnosis. "Until you're there, you can't stand in those shoes," she says.

Doctors put Hilary on an aggressive treatment regimen that included chemotherapy and a medication meant to boost the production of white blood cells to strengthen the immune system.

"I was very aware of the risk of sepsis," says Hilary, who completed her treatment successfully 17 years ago. "We need to be having conversations with people across society about the dangers of antimicrobial resistance for cancer patients and others."

Judith's story

As the head nurse of a neonatal intensive care unit, Judith is always on the look-out for signs of problems, including neonatal sepsis, the body's life-threatening reaction to severe infection. "One moment they seem to be improving and getting better, and in a matter of hours things change," says Judith.

In the case of sepsis, doctors must administer antibiotics quickly. Unfortunately, she and her colleagues have noticed that the standard treatments for neonatal sepsis are increasingly ineffective. Finding good treatment options is becoming harder and harder.

Helmi's story

Dr Helmi bin Sulaiman had carefully tended to his patient at the University of Malaya, Malaysia. He treated the man for life-threatening bacterial infections in his liver and bloodstream, and then an infection in his lungs. But now the infection had returned.

Dr Helmi was granted special permission known as "compassionate use" to treat the patient with a recently approved antibiotic that is not currently available in Malaysia. After a long recovery, the patient walked out of the hospital infection-free.

"This compassionate use programme has helped us a lot," said Dr Helmi. "But it doesn't solve the problem: I do not have access to the right medications."

Jemin's story

Just weeks before, the patient was a strong and healthy 25-year-old who farmed and drove a tractor in this region that is known throughout the world for its famous Assam black tea. Now he was unable to walk.

Dr Jemin Webster started running tests and eventually diagnosed the patient with melioidosis, a bacterial infection that is more common in the region than elsewhere.

Jemin administered antibiotics following guidelines, and slowly his young patient began to recover. However Jemin cannot take available antibiotics for granted: "One of the main challenges in treating bacterial infection here is the lack of availability of antibiotics, particularly the narrow-spectrum antibiotics," says Jemin.

Sergei's story

Together with countries around the world, Ukraine was badly hit by COVID-19. "Many patients were afraid of getting sick and dying, and insisted on getting antibiotics," says Sergei Petrik, a doctor in Mariupol.

Many doctors were scared too. Despite WHO and national guidance not to prescribe antibiotics for COVID-19, Sergei says some pushed ahead, risking antibiotic resistance. Then, as Ukraine was emerging from the pandemic, it was caught in the grip of war.

With injuries mounting and often unsanitary conditions, doctors turned to antibiotics to treat infections. But some of them no longer worked.

"Infection and antibiotic resistance came alongside the war. It's been a hard lesson to use antibiotics wisely," says Sergei.

Gregory's story

Pneumonia. Together with other lower respiratory infections, it is the fourth leading cause of death worldwide.

Gregory Carson, from Perth, knows this threat all too well. In the first half of 2023, he suffered from a bout of pneumonia that made him fear for his life.

"The antibiotic that saved me is 60 years old and cost less than US$5."

His experience motivated him to speak out about the need to develop the next generation of life-saving antibiotics.

"I'm aware of the issue of drug resistance. I wish all inexpensive antibiotics in developed countries had a levy to fund antibiotic resistance research."

Orum's story

When Prudence felt the first contraction, she knew something was wrong. "I was scared. I knew it was not time, but the baby was coming," she recalls. Rushed to the Kawempe Hospital, Prudence gave birth to her son Orum at just 24 weeks.

When doctors discovered Orum had pneumonia, they gave him a first-line antibiotic treatment intravenously. However, Orum did not immediately recover.

It took several rounds of treatment before he was discharged to continue recovery at home. Now Orum is healthy and ready to start school.

Astrid's story

Astrid was in labour at Geneva University Hospitals when she started to shiver and vomit and her temperature soared to 39.9°C. Doctors realized that she had a life-threatening bloodstream infection, and there wasn't a moment to spare.

"I had worried about my baby, but until then, I had never worried about myself," says Astrid.

Soon, Astrid was being treated with antibiotics intravenously, and she gave birth to a healthy baby girl. "Without antibiotics, I would not be here," she says.

Chelsea's story

When a drug-resistant infection swept through her COVID-19 ward, Chelsea found herself on the frontline of the COVID-19 pandemic and confronting an outbreak of drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumonia.

"Not only were patients battling with the virus, they then had to face a secondary infection on top of it, which could often not be treated because of antibiotic resistance," says Chelsea.

"It took COVID-19 to make me realise how crucial it is to have effective antibiotics."

Hassan's story

In southern Syria, expert nurse, Hassan Khatar, is working together with his colleagues to use antibiotics with care. When used wisely, antibiotics have made a huge difference to his patients.

“We must work together with international organisations to increase awareness of how to safely and correctly use antibiotics to prevent antibiotic resistance,” says Hassan, who has worked as a nurse in Syria for the past 30 years.

Hassan suggests that nurses and doctors should attend seminars and learn about new developments in the use of antibiotic treatments and care of patients. “Improving our knowledge and experience will lead towards a better and healthier life for patients.”

Honar's story

For over 30 years, Dr Honar Cherif has been treating cancer patients. For these patients, serious bacterial infections are a significant threat, with some needing several rounds of antibiotic treatments.

But in recent years, many countries, including those in Europe, are reporting increased antibiotic resistance.

"Infections caused by multi-resistant bacteria such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing (ESBL) bacteria do not respond to the broad-spectrum antibiotics we use to manage infections in these immunocompromised patients," says Honar.

"If we get to a point where we cannot prevent and treat these serious infections, we will have a very difficult time treating cancer with chemotherapy. This, of course, has catastrophic consequences."

Gustavo's story

How might you teach young schoolchildren about antibiotic resistance?

As a teacher in Cuenca, Ecuador, Gustavo Cedillo has drawn on ReAct’s Alforja Educativa—or "educational saddlebag" in Spanish.

"It allows children to discover the natural world of bacteria and the balance needed to care for human health and nature," says Gustavo.

In one of its games, children as young as 5 or 6 years old stand inside a circle and attempt to block children outside from getting in. The game simulates antibiotics that are unable to get into bacteria cells or are ejected from those cells (both of which are resistance mechanisms).

"During the first years of schooling the students are very perceptive and open to play, which makes it easier to capture their interest in discovery and exploration of nature," says Gustavo.

Daniel's story

Kenyan advocate, Daniel Waruingi, is shining a spotlight on one of the most pressing issues of our time….antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Together with a fellow student, he founded ‘Students Against Superbugs Africa’ to counter the threat of AMR.

As ‘AMR Champions’ young professionals and students in Kenya and other African countries set up AMR awareness initiatives in universities, colleges, schools, clinics and communities. Daniel and his team also offer support and training. Through their work, they’ve generated a wave of positive change.

"All of us are playing our part to improve our health and curtail the spread of antibiotic-resistant infections. Our end goal is to have a global youth movement, originated in Africa, to mitigate the threat of AMR," says Daniel.

Jeremy's story

Dr Jeremy Nel is the Head of Infectious Diseases at the Helen Joseph Hospital in Johannesburg, South Africa-one of the biggest hospitals in Johannesburg and one of the biggest HIV clinics in the world.

Over the past couple decades, he's seen huge progress against HIV/AIDS, driven in large part by free access to antiretroviral medications.

But future progress is in jeopardy.

"Antimicrobial resistance is one of the absolute top things that could set back progress in HIV patients. I mean we have the HIV drugs now-that's not the limiting factor. One of the things that might make things go backwards is AMR," says Jeremy.

Momipal's story

Drug-resistant bacteria isn't just affecting Momipal’s health, it is also threatening her family's livelihood. Having been repeatedly hospitalized by a series of infections, this has led to out-of-pocket expenses that are placing additional economic pressure on her and her family.

For a growing number of people this is the grim reality of the antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis. Not only is it already one of the world’s biggest killers, but over the coming decade it also threatens to push 24 million more people like Momipal into medical impoverishment.

Benz's story

Benz* lives and works in Thailand. Recently he met a man on an online dating app and they arranged to get together. After a great night out, they ended up having unprotected sex. A few days later, Benz realized something wasn’t right when he felt a sharp pain while urinating.

Feeling anxious, he was tempted to search for medication online, but then made a wise decision to see a doctor. Benz was tested for a sexually transmitted infection, diagnosed with gonorrhoea and prescribed antibiotic treatment.

"Looking back, I am proud of my decision to seek treatment early from a doctor. Thanks to antibiotics, I am cured from the infection."

*not his real name

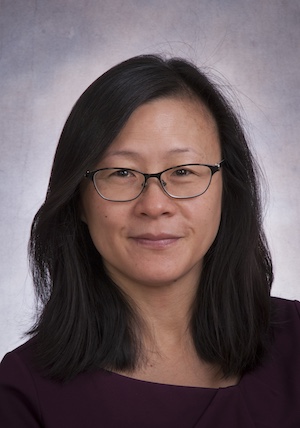

Lillian's story

As an oncologist at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in Toronto, Canada, Professor Lillian Sung specializes in treating children with blood cancer like leukaemia.

Although in recent decades, survival rates for this group of patients have increased, infections continue to pose a serious threat.

"Some bacterial infections are easily treated, and after a course of antibiotics, the infection is gone," says Lillian. "But they can also be difficult to treat and lead to significant morbidity. And in the very worst-case scenario, the child can die."

Prof Lillian Sung is part of the Union for International Cancer Control taskforce on antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and cancer care.

Tory's story

Tori Kinamon, a talented college gymnast in the US, feared the worst as she grappled with an antibiotic-resistant infection.

It started with pain in her left hamstring. A day later, Tori could barely walk. Doctors struggled to find the cause of her excruciating pain.

“The bacteria multiplied rapidly. I had an 18-centimetre abscess and an associated infection of the hamstring muscle. It was a very deep and severe infection, probably because it was not intervened upon earlier,” says Tori.

Inspired to study to become a doctor, Tori credits powerful antibiotics as being key to her eventual recovery.

“I was very fortunate there was an antibiotic available to treat my infection. It convinced me that we need to devote a lot of energy, brain power and funding to antibiotic development.”

Bhakti's story

What happens when antibiotics don’t work?

For Bhakti Chavan, this was not a hypothetical question but a reality. At 23 years old and living in Mumbai, India, Bhakti was diagnosed with extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR TB).

It took two years of treatment, including daily painful injections across several months, to be definitively cleared of TB.

Now as a clinical researcher and advocate for action on antimicrobial resistance (AMR), Bhakti is speaking out.

“AMR exists – it’s not a future pandemic. Without any prior history, I got infected with drug-resistant TB. If it can happen to me, it can happen to anybody.”

Nusrat's story

About ten years ago, Professor Nusrat Shafiq was charged with improving antibiotic stewardship at the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, a public hospital in Chandigarh, India. She started by taking a closer look at patients entering the intensive care unit.

“Patients were coming or being referred with all kinds of antibiotic prescriptions,” said Nusrat.

Soon Nusrat and her colleagues realized that overprescription and inappropriate prescription at the hospital was a widespread problem caused by multiple factors.

Since then, in line with newly launched antimicrobial resistance (AMR) action plans, their team has worked department by department to improve rational use of antibiotics. Their work is now a full-fledged programme that has led to as good or better patient outcomes as before. It has generated likely savings for hospitals and patients, as well as helped to preserve the efficacy of antibiotic treatments.

“The more success we have, the easier it is. The good stories travel across departments and beyond to other institutes and community healthcare settings,” says Nusrat.

Nour's story

Nour Shamas is a Lebanese infectious diseases clinical pharmacist and specialist in antimicrobial stewardship based in Saudi Arabia.

In September 2024, amidst Israeli attacks in Lebanon, Nour's mother Yusra* fled her home in Beirut to stay with her daughter in Saudi Arabia. Among the precious objects she packed: baby photos of her children and emergency antibiotics.

In 2018, Yusra got a life-threatening drug-resistant infection following emergency surgery on her back. Yusra recovered after months of treatment, but now she is particularly susceptible to recurrent serious drug-resistant urinary tract infections.

Increasingly the global community is recognizing what Yusra and her daughter Nour already know all too well: far beyond the hospital walls, conflict is contributing to the AMR crisis.

*Name has been changed for privacy.

Mirfin's story

For Prof Mirfin Mpundu, the heartbreak of losing his mother to a drug-resistant infection propelled him to dedicate his life to countering antimicrobial resistance, and in turn help save the lives of others.

“I’ve always believed that my mother’s death could have been avoided if they’d had the right antibiotics to treat her infection,” says Mirfin, whose mother died from sepsis a week after giving birth to his sister.

The tragedy was a turning point. Mirfin decided to study clinical pharmacy and public health and has since become a global voice on antimicrobial resistance.

As the co-founder of ReAct Africa, Mirfin and his team have helped governments to develop AMR National Action Plans. He has also mobilized young people all over Africa to raise awareness of AMR and the importance of access to antibiotics.

It’s hard to imagine life without antibiotics.

But, with drug resistance already one of the world’s biggest killers and rising, that’s exactly where we’re heading.

A global crisis needs a global solution.

Drug resistance doesn’t have to mean ‘Game Over’. All over the world, researchers, scientists, civil society and private organizations are taking steps to ensure that people get the protection they need from drug-resistant infections, today and for generations to come.

Together we can do more.

We all have a part to play. As part of this global effort, GARDP is working to support the development of essential new antibiotic treatments, and make sure that they are available to everyone who needs them.

Are you ready to take action?

Support

Our campaign

Pledge your support to raise awareness on drug resistance and the need to unlock new progress in antibiotic research, development and access.

Invest

IN OUR SOLUTION

Explore our investment case and find out how your government, foundation, company or institution can be part of our ground-breaking, non-profit solution.

Join

OUR COMMUNITY

Our REVIVE community is committed to sharing knowledge, skills and developments in R&D. Membership is open to students, academics and researchers alike.

Organizations across the world are joining the race to revive the power of antibiotics.

Will yours be next?

About GARDP

The Global Antibiotic Research & Development Partnership

To address the challenge of antibiotic resistance, we need to recognize the market and public health failures that have contributed to it.

Established in 2016, GARDP is the only organization in the world working to address both issues simultaneously. Driven by public health needs rather than profit, we work in partnership to develop new antibiotic treatments and expand access to them.